Why We Shouldn't Call Export Controls 'AI Safety'

And how conflating controls with safety undermines global cooperation

The blog has one simple message: export controls should not be AI safety. If you have never thought that these two are associated, I shall free you from this page. If this claim is contradictory to your belief, please give it a read.

This blog argues that the assumption of export controls as an AI safety conflate protecting humanity from existential crises with protecting the U.S. from strategic competitors. It pushes Chinese researchers away from safety collaboration and makes AI safety concepts appear like American geopolitical tools.

This isn’t an argument for or against export controls, nor is it about assessing the empirical benefits vs. harms export controls may provide. It’s an argument for rhetorically sparing export control from AI safety, for the sake of building the global cooperation that AI safety actually requires.

The Anecdote

“I am researching compute governance…wait, do you have a Chinese passport?” A girl whom I met at an AI safety networking event asked me right after we exchanged a few basic information about ourselves.

I nodded in confusion.

“Oh, I really want to get into several WeChat groups discussing China’s semiconductor shipments and progress, but I can’t access them.”

“Don’t you have a WeChat account?” another person chimed in.

“Yeah, it is impossible for me as a non-Chinese citizen to join, as WeChat has nationality restrictions1,” she looked at me.

“What?” I asked, still confused. Why are they telling me about WeChat groups tracking chip-related intelligence in China2?

“I think she wants you to join those groups and report back.”

This conversation happened last month. Both people work in AI safety.

This is a very weird conversation I’ve had, but it’s not the only one. In the past few months, people, after knowing that I research AI and China, have been very keen to connect me with researchers working on export controls. Others would ask if I know anything about Huawei’s chip production capabilities, or how many Chinese are smuggling chips, and in what ways.

For a long time, I did not know what was going on. I am visibly Chinese enough and do not speak perfect American English. Why would people so naturally think a person from China will help with export controls-related research?

It took me a long time to figure out what was happening: people thought that because I am concerned about AI safety in general, I supported export control. The link between “AI safety” and U.S. national security policy felt obvious to them—so obvious they never questioned it.

To me, the connection is far from intuitive. This is not a post calling for ‘no export control’—that debate is shaped as much by nationality and political position as by reasoning. In Chinese, we say “屁股决定脑袋” (“your butt decides your head” — your position shapes your perspective). My own seat means I would not want China to be “choked” to death by export control, just like Jensen does not want to lose his Chinese revenue.

There are too many writings on whether the U.S. should (or should not) have what kinds of export control at what point, and I cannot offer more useful insights. What matters to me is not whether one supports or opposes controls, but the deeper rhetorical shift: AI safety is increasingly being conflated with U.S. national security policy, especially regarding export controls on AI chips

The National Securitization of AI Safety

For this piece, I’ll follow Lin et al.’s definition of “AI safety” and “AI security” to make a distinction between the two [Note: While I personally view AI safety as encompassing both near-term harms and existential risks, I’ll focus primarily on the existential dimension here.] The key distinction is this: AI safety research assumes the AI system itself may fail or behave unexpectedly, while AI security research assumes human adversaries seeking to exploit or manipulate the system.

It’s also important to distinguish AI security from U.S. AI security (i.e., U.S. national security on AI). Each country has its own AI security priorities—shaped by different threat models and adversaries—that may align with or diverge from U.S. interests. Export controls fall specifically within the U.S. national security framework for AI, which represents the U.S. strategic approach, rather than the global agenda.

Recently, however, the rhetoric around export control has grown beyond a mere U.S. national security issue. Leading AI safety-minded think tanks now position semiconductor restrictions as a main area of their research focus, with policy researchers regularly publishing articles that link export controls to risk mitigation. There is also more technical work specifically on mechanisms for control compliance.

This coalition between safety advocates and national security actors has blurred the line between technical AI risk and geopolitical risk, such that ‘AI safety’ increasingly signals alignment with American national security objectives.

The challenge isn’t that these policies necessarily undermine technical safety research—work on alignment, interpretability, and robustness continues regardless—but that the rhetoric increasingly conflates protecting humanity from AI with protecting the U.S. from strategic competitors. While almost all existential AI safety concerns have national security implications, assuming that U.S. export controls automatically enhance global AI safety oversimplifies both technical and geopolitical realities.

A Global AI Safety without China?

When export controls are branded as “AI safety,” the implicit message is: China is an inherent threat to AI safety that must be contained rather than engaged. This framing treats Chinese AI development as fundamentally unsafe and positions U.S. restrictions as humanity’s protection against Chinese recklessness. (There are many factors behind this belief, many ideological. To avoid my substack becoming another “CCP bad or not” battlefield, I’ll exercise some self-censorship to focus only on AI safety.)

But this narrative ignores evidence that China is taking AI safety seriously. From June 2024 to May 2025, Chinese scholars published ~26 papers on technical AI safety, more than double the output from the previous year. Most leading Chinese foundation model developers have signed voluntary “AI Safety Commitments.” The newly published AI safety governance framework 2.0 mentioned “AI self-awareness and loss of human control” as a main risk. While China’s progress in safety isn’t as strong as that of leading Western countries, the trajectory suggests promising movement toward (existential) AI safety commitment. However, this momentum risks reversal when “AI safety” becomes synonymous with “containing China,” starting from broken trust between Chinese researchers and existential risk-focused AI safety communities.

An Impossible Pair: Export Control and China Engagement

Mistrust usually accumulates at an everyday level that most people don’t see. It seems to me that promoting export control and engaging China on AI safety are contradictory initiatives. Or worse, both initiatives stem from fear that China is developing frontier AI for evil purposes—that China is a threat. I’m probably not the only Chinese person who links export control to China hawks. Many Chinese people, including AI researchers concerned about safety, may react similarly.

Admittedly, this intuition isn’t always accurate. Many export control researchers seem friendly after a few conversations. U.S. think tanks sometimes frame things in hawkish language to get attention while privately valuing collaboration. Technically, there are ways to engage Chinese researchers on safety topics while export control continues.

But rhetoric matters. I find it hard to separate “export control” from “AI safety engagement” neatly. For me, sitting in an export control lecture feels like waiting for someone to throw me out the window. It takes enormous effort to believe someone will speak respectfully while discussing how every Chinese person is smuggling chips in their backpack to hand over to the army (which itself is absurd).

This is partly because Chinese state discourse frames export control as 科技霸凌 (“technological bullying”): the U.S. using semiconductor dominance to strangle China’s development. Export controls are particularly vulnerable to this framing because, unlike sanctions tied to human rights violations or military aggression, chip restrictions lack a clear moral justification beyond strategic competition. When the stated goal is preventing China from achieving technological parity rather than stopping specific humanitarian harms, it’s easy to characterize the policy as pure power politics.

Once export control enters the rhetoric of “bullying,” it often gets linked to China’s “centuries of humiliation,” invoking historical memories of the Opium War, Eight-Nation Alliance, and Japan’s WWII invasion. These historical experiences remain significant in Chinese public discourse and can contribute to defensive responses, including viewing foreign policy initiatives with suspicion and seeing frontier technological development (i.e., more advanced AI) as essential protection against future vulnerabilities.

You cannot undo that chilling effect by saying “we mean well.” You won’t even have a chance to say it. Assumed hostility from export control alone is enough to kill relationships before they can grow.

The ‘AI Safety’ that Harms AI Safety in China

The damage goes beyond personal mistrust. Export control makes it harder to disseminate related safety ideas within China’s AI ecosystem. Compute governance and international verification are important safety fields, but because they’re linked to chip controls, they immediately appear suspicious. How likely are Chinese researchers to trust chip verification advocates arguing for on-chip trackers when Washington’s discussions already trigger Beijing’s concerns about H20 backdoors? How convincing is it to promote “know-your-customer” rules for data centers when Chinese people increasingly worry about being cut off from Western cloud services?

Conflating export control and AI safety also distorts how the Chinese public understands AI safety. People will probably not embrace the broader AI safety concept when part of it seems designed to prevent China from developing frontier models.

The result is that AI safety itself becomes politicized in China. Instead of being seen as a universal concern, it looks like an American agenda. This politicization undermines the possibility of building shared standards. Emerging voices in Chinese discourse now view AI safety advocacy (even Geoffrey Hinton’s WAIC speech) as serving U.S. interests rather than addressing genuine risks.

The World Does Not Revolve Around Washington

The assumption that export control equals AI safety reminds us to reflect on our positioning as individuals, especially those who want to benefit all humanity: how U.S.-centric are our mindsets?

This assumption might work well if one only works with colleagues who are American, citizens of the U.S.’s traditional allies, or people who have immersed themselves in U.S.-centric ideology. But if you want to bring China, or other non-U.S. allies, to your AI safety table, I’d recommend being more careful with messages that can be read as geopolitical.

Here are some good practices for non-Chinese AI safety researchers who see the value of China engagement:

Do not talk about export control in your first few conversations with a Chinese national, regardless of whether you think they support the Chinese government.

Do not send your export control research to Chinese researchers’ inboxes for collaboration/review—and perhaps be careful about “compute governance” and “verification” ones too.

More generally, do not ask what they think about the party if you are not their best friend(s) forever, and do not assume that any Chinese person is pro/against their government—things are far more complicated than black-and-white.

The same applies to people from other non-U.S. ally countries. In general, it’s good to be mindful of one’s geopolitical position even when talking about what you think is purely “technical”, recognizing and respecting that others may hold different views.

Chips are chips, and export control is export control. They may advance national interests, but that’s different from advancing global safety. It’s fine that people work on various export control mechanisms for the sake of American (or personal) interests. Just please don’t call this research AI safety—for the sake of AI safety.

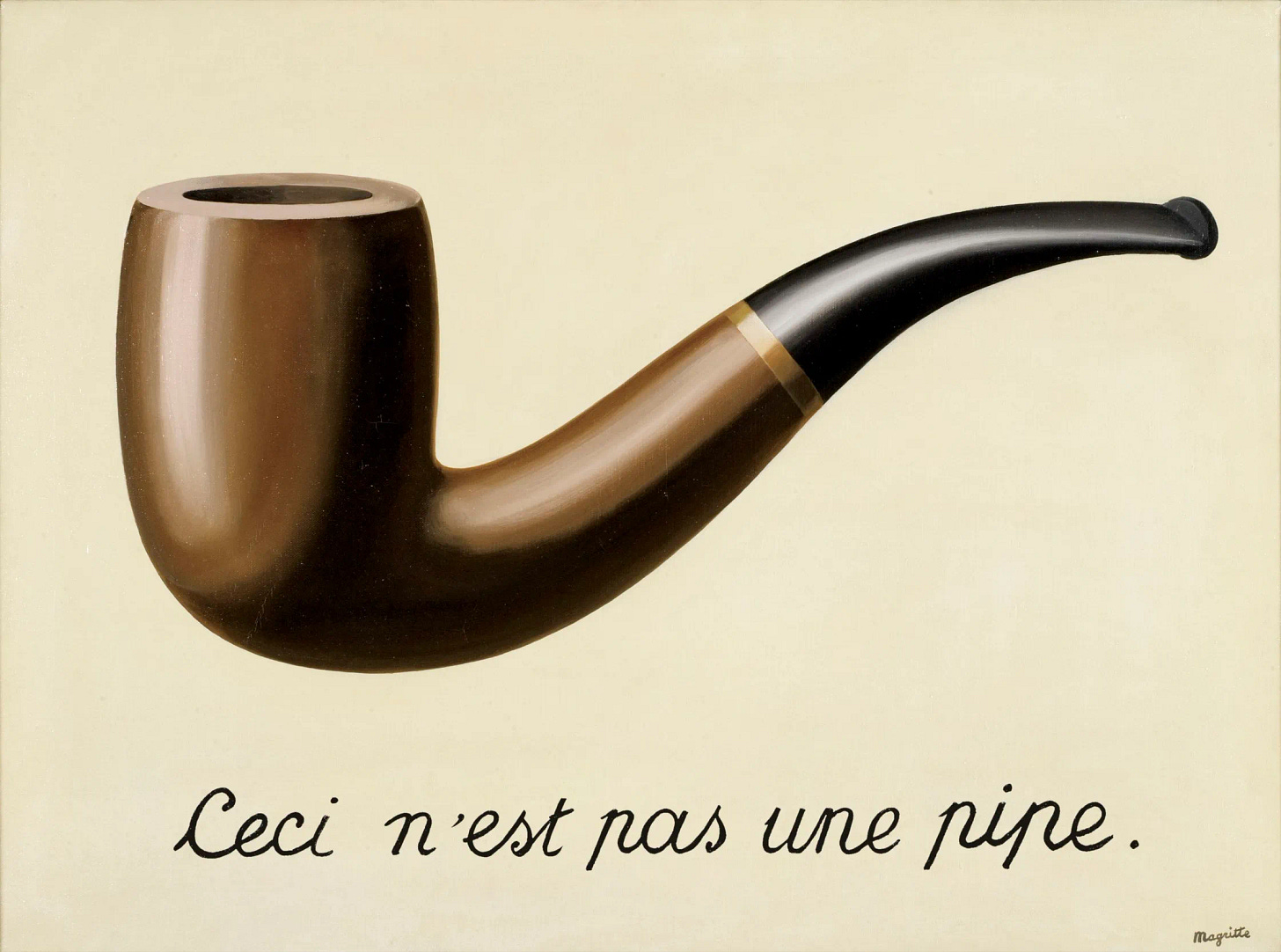

René Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images” (1929) depicts a realistic painting of a pipe with the text “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (”This is not a pipe”) written below it.

Acknowledgement:

I am grateful to the Asterisk AI Fellowship for supporting this work, and especially to Clara Collier, Max Nadeau, and Lawrence Chan for encouraging me to write on this topic and helping improve the clarity of my arguments. While this piece is far from perfect, I hope it contributes to more nuanced discussions about the relationship between AI safety and geopolitical policy.

I did not know any related nationality restrictions before.

After the publication, the person later clarified her interest was technical curiosity about semiconductor supply chain developments. I probably misunderstood her intent. But the fact that “tracking China’s domestic chip progress” and “monitoring how components reach China despite export controls” can describe the same activity—just framed differently depending on one’s position—illustrates the problem. What feels like neutral technical research from one perspective can feel like strategically motivated intelligence gathering from another.

Thank you for putting some of my feelings into words, Zilan! Many instances when I mention I want to do “China-related work” people send you to the export control corner

I agree with your post, but I also get why export controls are often associated with AI safety, particularly the 'AI notkilleveryoneism' part of AI safety.

So my understanding of the thesis is that we will create AGI, and AGI will kill everyone. What can you do about it? You can either solve alignment and make sure AGI doesn't kill everyone, or prevent AGI from being created until the former happens. What makes AGI happen sooner than later? Race dynamics. More specifically, if two or more entities are close to the frontier, then they will race harder. If there's only one entity at the frontier and everyone else lags behind, then they can chill (relatively). If you see 'US' and 'China' as meaningful entities, then slowing down the number 2 (i.e. China) could meaningfully slow down AI progress, and it would directly contribute to this version of AI safety by not accelerating the race towards AGI.

But different actors have different agenda, and national security folks have increasingly been part of the conversation, so this argument has picked up a flavour of "let's slow down China because US needs to remain the best country in the world".

I guess the root of the problem is that as with any pre-paradigmatic field, the field of 'AI Safety' is ill-defined and nebulous, and different people have different visions of the field, so certain things gets lumped under the field and jeopardizes all sorts of other things.